Winter 2020: Experimental design for CO2 x heatwave effects in Pacifc herring early life-satges

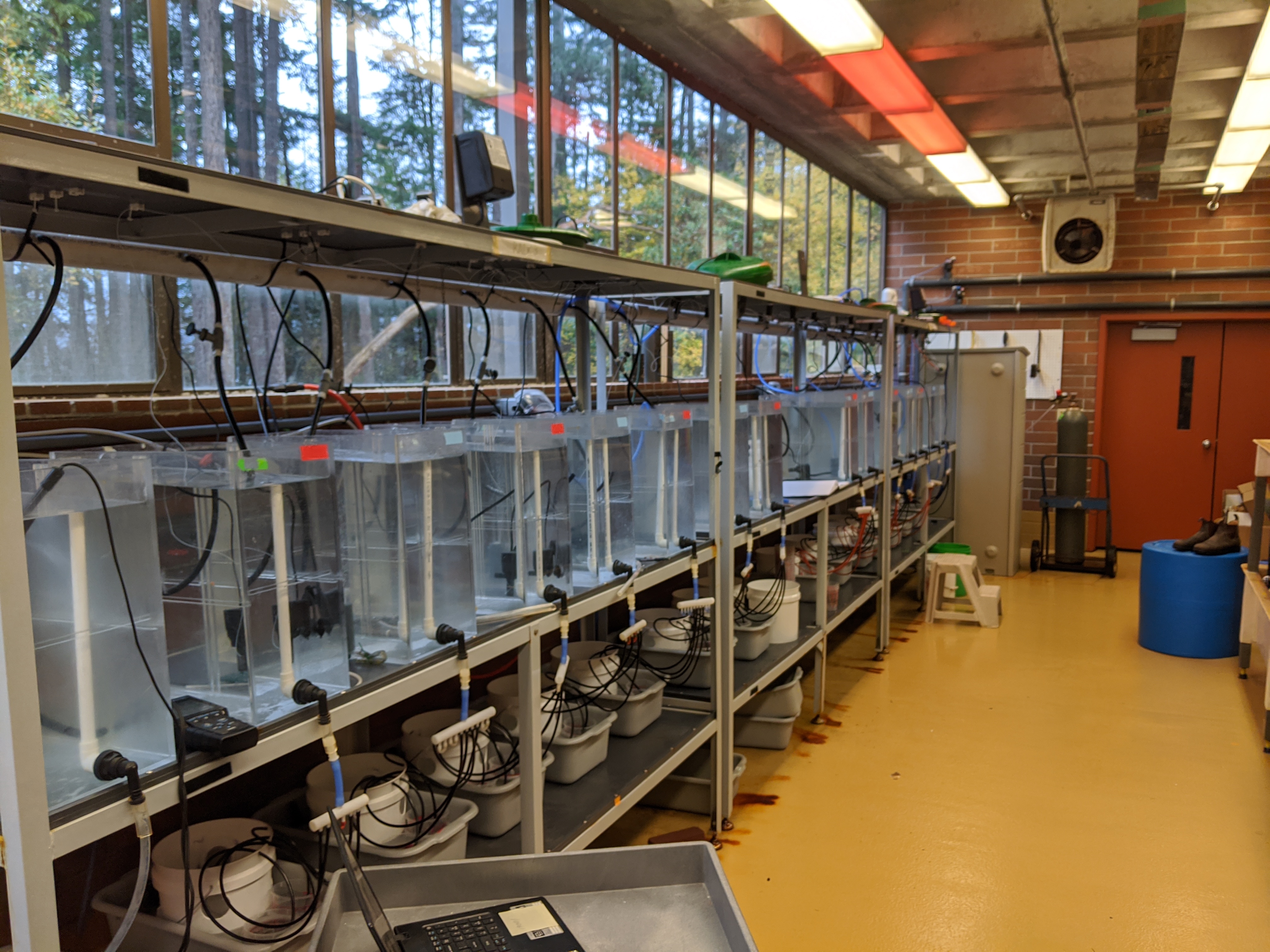

Experiments were conducted at Shannon Point Marine Center in Anacortes, WA. Embryos and larvae were reared in 16 independent flow-through units composed of a 40 L elevated header tank and a 15-L rearing container situated below the header tank. Embryos were reared in customized 1-L polyethylene baskets fitted 300-um flow-through mesh that were floated in the rearing containers.

I employed a 2 x 2 CO2 x temperature experimental design (N = 4 replicate tanks per treatment level). Two pCO2 conditions were achieved (~500 and ~2500 uatm). The high CO2 level was achieved by bubbling 99% CO2 into half of the header tanks. CO2-stripped air was bubbled into control pCO2 tanks to maintain ~500 uatm. CO2 treatments were split into two temperature regimes: ambient and heatwave. Initially all tanks were maintained at ambient temperatures until 5 days post-fertilization (dpf) when a heatwave was initiated in half of the tanks per CO2 treatment. Temperatures were increased by ~0.9°C/d for 5 consecutive days to achieve a heatwave condition of +4.4°C above ambient (8.7°C to 13.1°C). See this post for a more detailed description of the heatwave treatment.

Fertilization

On Feb 19 gonads were dissected from 12 wild adult herring (9 females and 3 males) collected by Washington’s DFW (thanks Jim West!) On Feb 19 gonads were dissected from 12 wild adult herring (9 females and 3 males) collected by Washington’s DFW (thanks Jim West!). Gonads were stored in glass dishes covered with moist paper towels and stored at 4.5°C for 48h. Fertilization commenced on Feb 21 following protocols established by Dinnel et al., 2010. Four large plastic dishes (twp per CO2 treatment) were filled with 750 ml filtered and autoclaved seawater (salinity 32) adjusted to 500 or 2500 uatm pCO2. They were lined with 300-um nylon mesh screening. Fertilization took place at 8.5°C in a temperature-controlled room. Five 1-cm square sections of teste were sampled from each male and were eviscerated together on 300-µm screen. Milt was filtered into a 1-L glass beaker filled with clean seawater. The milt-seawater mix was split into two 500-ml beakers and the pCO2 level was adjusted to 500 or 2500 uatm pCO2. Then, 250-ml of milt-seawater per CO2 level was poured and gently mixed into each spawning dish. Next, ovary membranes were gently sliced opened, and I used a small silicon spatula to scoop a few eggs at a time and deposited them into the spawning dishes by with a quick sweeping motion through the water. Eggs from each female were randomly distributed to each spawning tray until the screens were largely covered with a single layer of eggs. Eggs and milt were left so soak for 1 hr.

Screen were then rinsed with clean seawater to remove milt and unattached eggs then were soaked in a 100-ppm solution of Povadine in seawater for disinfection. Screens were than cut into smaller sections and distributed to one of four replicate tanks per treatment level.

Sampling design

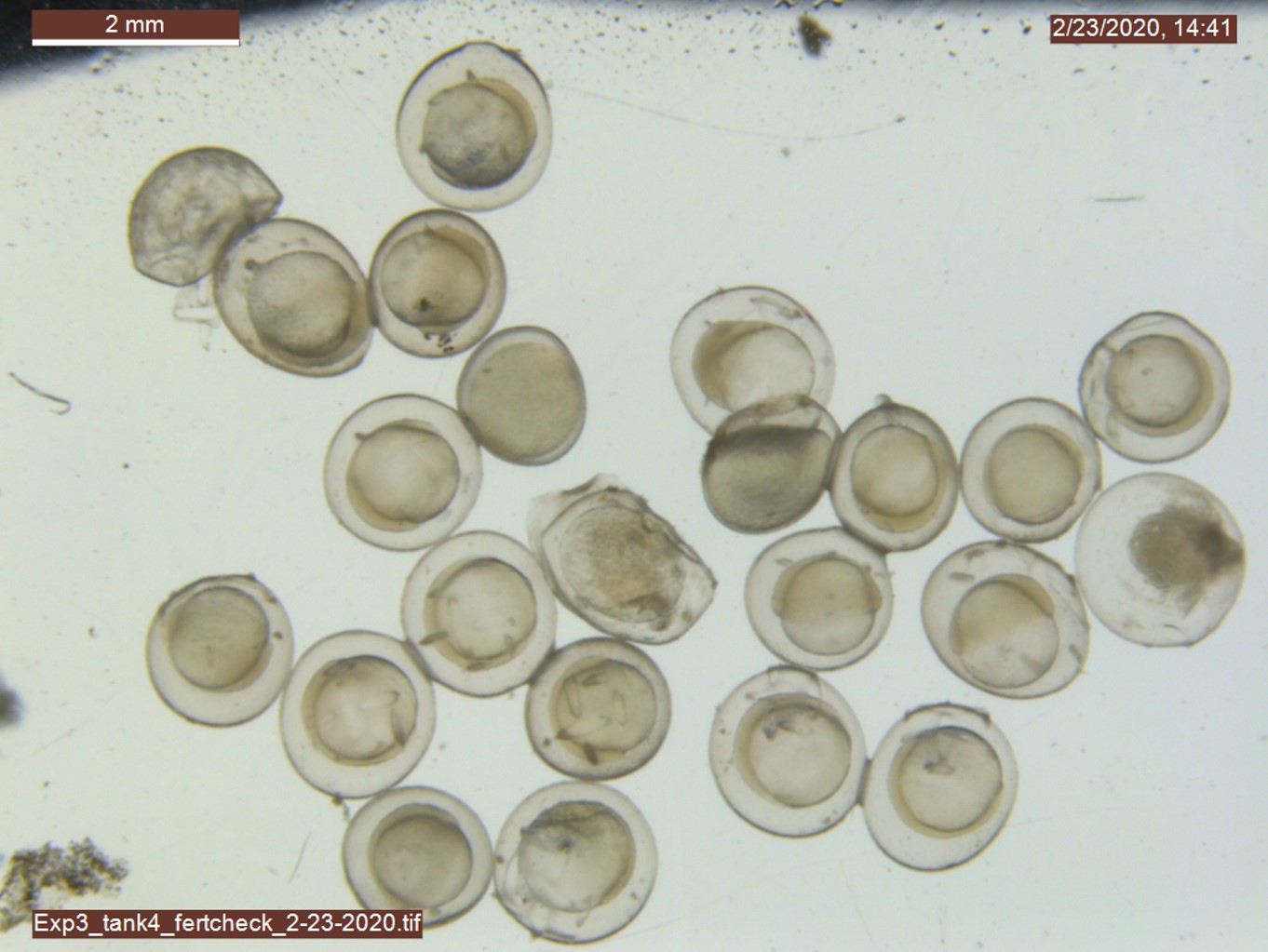

Fertilization success: After 12 hours post-fertilization (hpf), N > 20 embryos were randomly sampled from each tank and photographed (at 80x) to quantify fertilization success. Fertilization status was determined by the presence or absence of a raised fertilization membrane (Dinnel et al., 2010) and tank-specific fertilization success quantified as the percentage of fertilized eggs by the total sample size.

Embryo survival: After 14 hpf, I selected 100 fertilized embryos (confirmed under the dissection microscope) distributed them to a new rearing basket within each tank to quantify treatment effects on embryo survival. The remainder of the embryos were maintained in a separate basket for measurements of developmental and metabolic rates. Hatching commenced 10- and 13-days post-fertilization (dpf) in the heatwave and ambient temperature treatments, respectively. Each morning, newly hatched larvae were counted and removed from the survival baskets and I evaluated them under the dissection scope for obvious developmental deformities (following Dinnel et al., 2010). In some cases, newly hatched larvae were dead or dying at the time of sampling. Hatchlings were considered dead/moribund if they failed to react to gentle prodding with tweezers and a bright light stimulus. For each tank, I quantified total hatch (total number of hatchlings by 100 starting embryos), healthy hatch (total hatch minus the sum of dead, moribund, and deformed larvae all divided by 100 starting embryos), and deformed hatch (number of deformed larvae divided by 100 starting embryos). The embryo survival portion of the experiment was terminated 18 dpf when no new hatchling had been counted for three consecutive days at which point any unhatched embryos were counted. I confirmed that all unhatched embryos were confirmed to be dead by examining them under a dissection microscope.

Embryo Oxygen Consumption: Rates of embryonic oxygen consumption were measured 6, 7, and 8 dpf. I sampled 10 embryos from each replicate for measurements